| By Kim Gilhuly |

In mid-September, I attended A Women’s Gathering on Criminalization and Community Health Inequities. The gathering was different in many ways, but one aspect of it really stood out: We were being invited into a community that most of us knew very little about, a community of women who had been incarcerated at some time in their lives.

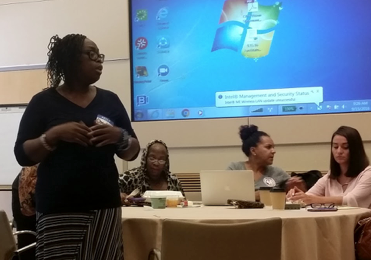

Charlene Sinclair, Center for Community Change, speaking at A Women’s Gathering on Criminalization and Community Health Inequities.

As Andrea James, founder of Families for Justice as Healing and The National Council of Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls (The Council) said, “I am a former lawyer, a community activist, the wife of a man who was incarcerated, an active resident of Roxbury, MA, and a mother. I have a lot of professional and personal experience. But I didn’t become a expert until I was incarcerated.”

Only now am I beginning to understand this reality. For the past two years, I’ve been researching the health and equity impacts of the criminal justice system and working with advocates to create a new system, one that puts health and wellbeing, instead of punishment, at the forefront. Some of the people I collaborated with had been incarcerated, and I felt as if I had some understanding of how the criminal justice system destroys people and families.

But, really, it wasn’t until September 15, 2016—when 30-plus women who had been incarcerated met with about 15 women who worked in the field of public health—that I became more profoundly and intimately connected to those experiences and impacts. The women I met drove home the urgency of needing to work together to create a system of justice that values every life, treats people with dignity, demonstrates compassion, promotes a restorative and rehabilitative approach, creates space for accountability, and improves both health and safety.

And particularly for women and girls.

The reality hit me that, as women, we all have some degree of familiarity with the conditions that led to the women being incarcerated. While I had not had the experience of being incarcerated, I had experience with many of the pre-cursors—and that was a connection I had not made until hearing their stories.

Consider this: No woman is immune to the threat of community violence, oppression, being judged by her looks, being harassed on the street. And so many of us women (1 out of every 3) have been physically, psychologically, or sexually abused. And out of women who become incarcerated, that number is even higher—a recent Vera Institute report showed that 85% of women in jail have been physically or sexually abused.

What I heard from the women who shared their experiences is that these exposures (as we say in public health) —combined with acute and ongoing bias, mistrust, and maltreatment among many government agencies and institutions—led to them making choices that were ultimately criminalized. Behaviors that a more humane society would respond to with an offer of support, healing, and recovery—were instead met with surveillance, arrest, and incarceration in the United States.

But while I felt a connection to those exposures, it became deeply clear that we experienced a different, and unequal, set of outcomes based on things like racism and where you live. My childhood and home life weren’t perfect and I had some of the same teenage behaviors that I heard about in the room. But growing up white, in a suburb, middle class—these worked in my favor. People—rooted in institutions and systems—gave me leeway to make mistakes and gave me second chances. That is what privilege looks like, and that is where much of my experience diverged from the women in the room. Being confronted with that in an honest and face-to-face dialogue was so important to our ability to establish trust and try and build an authentic partnership.

Another thing happened that also stretched my understanding of what it takes to build trust with communities who have experienced significant trauma. The public health women in the room, many of whom work in government, were held responsible and asked to own the fact that we worked in and with institutions that repeatedly harmed, alienated, and failed the formerly incarcerated women throughout their lives. The level of distrust that existed in the room—understandably—was, well, rough. But my level of respect and admiration for every single woman in that room went through the roof after hearing their honesty and their doubts. I had such respect for women who are formerly incarcerated for getting themselves to that room, sharing their stories, calling out institutions for failing them, but also having hope that we can work together. And I had such respect for women in public health who listened with compassion and anger at the stories of women, who were not offended by the call to be accountable for the sins of government, and who eagerly asked “What can we do? To help repair the harm.”

It was a full day. It was a day like no other I have ever had in my 20+ years of public health work. The Women’s Gathering on Criminalization and Community Health Inequities was a beginning and we are now figuring out what we can do together. Lots of ideas emerged: new research and advocacy campaigns, new collaborations and capacity-building efforts, invitations into our institutions to humanize each other. It is on all of us now to continue to build this fledgling trust.

To be explicit about my gratitude: thank you to all the women who attended from The Council, women who are formerly incarcerated but may not be part of The Council, and all the women from the public health institutions. Your open hearts and minds is what made the day such a meaningful experience.

And a special thanks to our Women’s Advisory Team who helped plan the gathering: Jeanne Ayers (Minnesota Department of Health), Solange Gould (California Department of Public Health), Donna Hylton (The Council), Paula Tran Inzeo (University of Wisconsin Extension and THRIVE Wisconsin), Andrea James (Families for Justice as Healing & The Council), Marilyn and Pamela Winn (Women on the Rise & Georgia Racial Justice Action Center)—and especially to Charlene Sinclair, Caitlin Dunklee, and Cindy Eigler from the Center for Community Change for organizing the gathering and including HIP as co-conveners. Thank you all!